|  |  | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|  |  | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

Техническая поддержка

ONLINE

|  |  | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

Inflation, deflation, and capacity utilization | Finance & Capital Markets | Khan Academy

ruticker 08.03.2025 21:05:03 Recognized text from YouScriptor channel Khan Academy

Recognized from a YouTube video by YouScriptor.com, For more details, follow the link Inflation, deflation, and capacity utilization | Finance & Capital Markets | Khan Academy

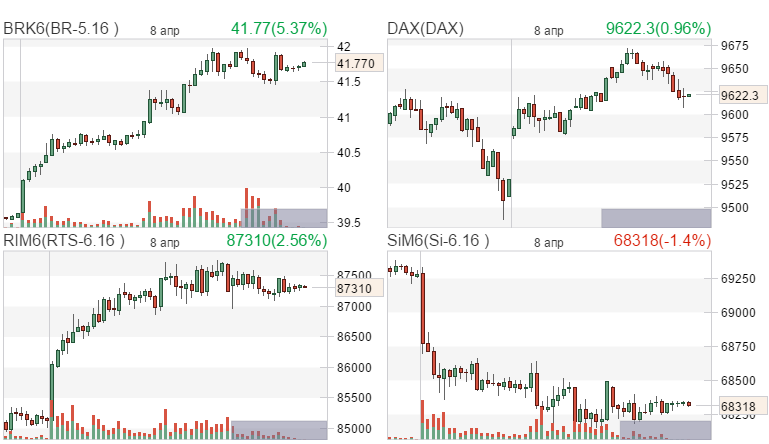

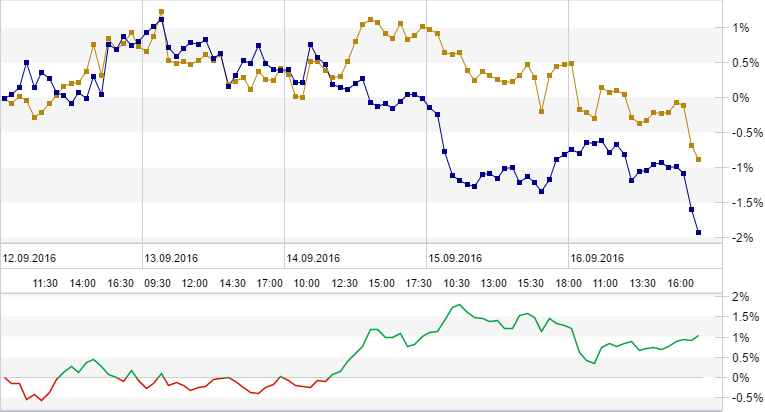

With all the talk of the deficits that we're entering, the stimulus bill, and all the money that's being spent on the bank bailouts and potentially the auto bailouts, the question that everyone's asking is: **Is this going to lead to inflation?** That is what I hope to address in this video. I guess a good starting point is: **What is inflation?** It's a general increase in the price of goods and services. They actually measure it by taking a basket of goods and services and seeing how those prices compare to a reference year. If those prices go up by 3%, they might use a consumer price index and say inflation increased by 3%. So, that's what inflation is. The opposite of inflation is deflation. If one year, a 10 megabyte RAM costs X dollars, and then the next year it costs a little bit less, it's actually a deflationary process at least in that market. With those definitions out of the way, let's talk a little bit about what causes it. A couple of days ago, I made these videos on cupcake economics where I talked about what happens when the cupcake factories have high utilization or low utilization and what that might mean for prices. The reason why I did that is because I really wanted to make it very clear that it really is the utilization of factories or of people that drives prices. So, if I have, let's see, if this is all of the capacity that I have (and when I talk about capacity in this video, I'm speaking in very general terms—it's all of the goods and services that we could produce), we could just talk about labor capacity. The unemployment rate is a measure of what is essentially not being utilized. But let's just talk about that; this is just our capacity, our productive capacity. In those cupcake economics videos, I showed that if the demand is pushing up against capacity—let me do demand in a different color—if demand is really close to capacity, and I know everything I draw kind of looks like balance sheets, but this isn't intended to be a balance sheet; this is intended just to show you that demand is pushing up against capacity. So, in this situation, let's say this is capacity. If demand is at 90% of capacity, then the people with the capacity might say, "Gee, instead of trying to just sell that extra unit and have to worry about all the raw materials and have to work for that extra unit, why don't I just raise prices?" Right? When there's high utilization—let me write that down—**high utilization of capacity leads to prices increasing.** This isn't some kind of fancy macroeconomic principle; it's true. If you're running a lemonade stand, if all of a sudden you're starting to sell 95% of your lemonade, you'll probably say, "Hey, maybe it's worth it if I raise the price." On the other hand, **low utilization**—let me pick another color—**low utilization will lead to prices dropping.** You go back to your lemonade stand and you say, "Wow, you know, if I'm only selling 20% of the lemonade that I make, maybe my problem is that my lemonade's too expensive." Frankly, if there were a bunch of lemonade stands, and everyone is trying to sell their capacity, just to compete with each other, they're all lowering prices. Actually, I'll throw another thing in here that's a little unrelated to inflation, but high utilization makes prices go up, and it also makes people want to add more capacity. So, investment goes up—both of those things to add more capacity, but we won't worry about that right now. If you accept that, and I think it's a reasonable argument because it's really based on, I think, common sense, then I think you'll buy the argument that if you have very low utilization, it's difficult to have inflation. Likewise, if you have very high utilization, it's hard to avoid inflation. To kind of hit the point home, I actually took our company's Bloomberg terminal and copied and pasted these charts here. The orange line— I know you can't see it that well on YouTube, so I'll try to make it clear with my drawing—this orange line shows capacity utilization. The starting date right here was, I think, it was 1967. This is 1969, roughly December 31st, 1969. So, this is 1970, the beginning of 1970, this is the beginning of 1980, the beginning of 1990, and this is 2000. This orange line represents capacity utilization. Up here, this is 90% utilization, and then down here, this is 70% utilization. If we look here in the late '60s, we had very high utilization, arguably because of the Vietnam War. We had factories running at capacity to build bombs and Agent Orange and God knows what else. Then utilization went down. The interesting thing—well, actually, before I go into kind of what happened, let's think about what this white line is. So, the orange line is utilization. Up here, we had like 90% utilization. Very recently, this was like 2007; we had 80% utilization. Then very recently, utilization has dropped off, which essentially means we're not running our factories at full tilt. This white line is year-over-year inflation growth. Let me do that in white. This is year-over-year inflation growth, and actually, let me draw a zero line so we can separate inflation from deflation. So, let me see—zero inflation is right over here. That's zero inflation. You see in this time series that we've never had zero inflation, although we have had periods of very high inflation. The interesting thing, just following into the cupcake economics and this whole notion of capacity utilization, is that inflationary periods are always preceded—at least all the data I have—by increases in capacity utilization. You can view this as the beginning of a pretty significant inflationary uptick in prices, right? Notice it was preceded by an uptick in capacity utilization. So, if you saw right here, wow, capacity utilization is starting to go up. Another interesting thing is to see what threshold of utilization starts to trigger inflation. Over here, you say, "Okay, when inflation really started turning around, we were at a capacity utilization of roughly, I don't know, 83-84% right there." If you look at the next period where inflation really started to hit, you could either pick that point or that point. Where was capacity utilization? It was around that same level; it was right there. It was above 80—this is about 82%. We could pick every period before that. So, when did inflation really hit? Well, you know, since then, inflation really hasn't been a major problem. These are our two major bouts of inflation in the early '70s and in the early '80s, and those were when we had extremely high capacity utilization—extremely. So, the point I want to make here is **capacity utilization really is the driver of inflation.** You could actually find it the other way around. This white line here—you don't see it because the orange line—oh, actually, I realized that I'm showing you off of the screen. But let me actually reduce my window so I can show you. So, this is more recent, where we see that capacity utilization started falling off. I think this is in the summer of 2007. You don't see it there because it's overwritten, but the inflation line has also dropped considerably. It comes down to here, but notice once again, utilization dropped off, although here it's pretty close, but utilization dropped off a couple of quarters before inflation dropped off. That's why I always wonder why the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, they always talk about different inflation indicators and what to do about interest rates when you do have a pretty good indicator, and that's capacity utilization. Now, the next question that everyone has: "Okay, fine, capacity utilization drives inflation. We can all buy that. But clearly, what's going on right now is kind of just a wholesale printing of money. Won't the wholesale printing of money drive demand to go up, and then we will have very high capacity utilization, and then we'll have inflation or even hyperinflation?" My argument there is that's normally the case. Normally, if you increase the money supply, that should increase demand. But there's a subtle—and it's almost a philosophical point—but it's an important one to realize: **Money just allows you to express demand.** Let's say I really, really want to buy a Rolls-Royce; I just don't have the money. If someone gave me $200,000 into my pocket, then I could express that demand to buy the Rolls-Royce. On the other hand, let's say I have everything I need—I'm happy with my Honda and my two-bedroom apartment—and someone gave me $200,000. So, they've increased at least my money supply. Will that increase the demand for the Rolls-Royce? No. I have money to express demand, but I won't do it just because I don't think it's necessary. You can make that same analogy in the economy as a whole, where you can imagine an island where, let's say, there are five of us—or let's say three of us because I don't want to draw five people—and between us, we use seashells as a currency. We're very confident, and you know, maybe I'm the builder, and this guy's the fisherman, and she's the farmer. In one year, I use a seashell to get some fish, and then he uses that seashell to buy some crops, then she uses that seashell to buy a house, and I use the seashell again to buy more fish. You can see that that one seashell, even though my money supply on that island is one seashell, can transact many times in that year. So, the velocity in this example is very high, right? Now, you notice that my expression of demand happens in these actual transactions. I not—well, I'll go to kind of the classical money supply equation soon—but you can imagine another reality where, for some reason, I stop trusting this guy. I become very cautious and I say, "Well, you know what? I don't want to give him my seashell because I'm not sure if I'm going to get that seashell back again to do something else." You can imagine a reality where the central bank of our island all of a sudden finds hundreds of seashells and puts seashells in everyone's pockets. So, we're all full of seashells, but all of us have just lost so much confidence in the economy or are so unsure over whether other people are going to use my goods and services that I don't want to use their goods and services. So, we all just start hoarding seashells. This is a situation where the money supply could actually increase pretty substantially, but since no one wants to express it through demand, it's not going to increase utilization. So, in the situation that we're in right now, if you're wondering about whether you're going to see inflation or deflation, my argument is: **Look at capacity utilization.** People can point to the money supply; they could say that, "Oh, you know, money supply," and this is the classic kind of money supply equation that the money supply times the velocity of money—that's how often the actual dollars switch hands—is equal to the average price of goods times the total quantity of goods and services we have. Most people say, "Wow, if the money supply increases, then won't prices increase?" Well, that would be true if you assume that velocity and quantity are constant. But we're saying that whenever you have major shocks and people lose confidence, this velocity can slow down considerably, especially when things like financial intermediaries start hoarding money and people start putting money into their mattresses. In fact, oftentimes, people don't even consider things that aren't being transacted money. For example, those commemorative coins that they sell on TV are not considered part of the money supply because people don't use them as money. Anyway, I'm all out of time. I'll continue this discussion in the next video.

Залогинтесь, что бы оставить свой комментарий