|  |  | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|  |  | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

Техническая поддержка

ONLINE

|  |  | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

Inflation, deflation, and capacity utilization 2 | Finance & Capital Markets | Khan Academy

ruticker 08.03.2025 21:05:03 Recognized text from YouScriptor channel Khan Academy

Recognized from a YouTube video by YouScriptor.com, For more details, follow the link Inflation, deflation, and capacity utilization 2 | Finance & Capital Markets | Khan Academy

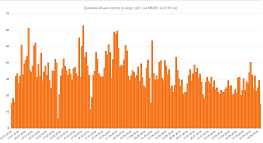

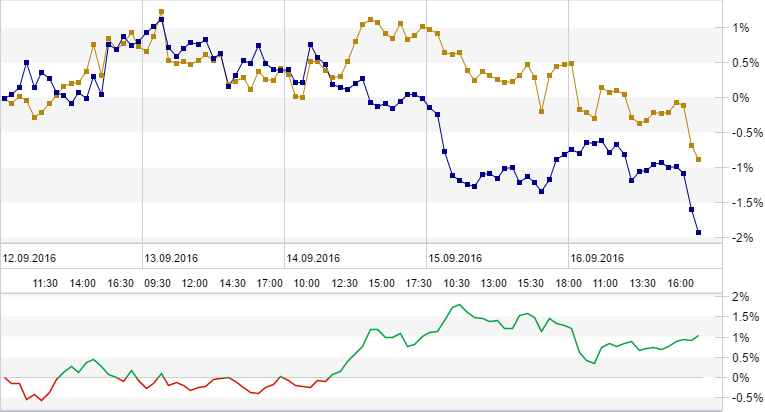

In the last video, I spoke a bunch about the determining factor on whether we have inflation or deflation. It isn't so much the money supply, although the money supply will have an effect; it's really **capacity utilization**. Capacity utilization is driven by demand, and I made that distinction because, you know, I gave that example of the island where you could have a very small money supply, for example, one seashell. But if the velocity is really high, then people are expressing that demand, and you'll have very high utilization of all of the capacity on the island. You might have inflation even though the money supply is one seashell. On the other hand, let's say we found a bunch of seashells, but everyone stops transacting, so the velocity slows down a bunch. In that case, even though the money supply is huge or, you know, a lot larger than it was, people aren't expressing demand. So demand will be a lot lower than capacity. As we showed in the **cupcake economics video**, when you have a lot of unused capacity, it's everyone's incentive to kind of try to sell that extra unit, and they all lower prices. So you could have an increased money supply, but if the velocity slows down or if demand is slowing down—because that's what's causing the velocity to slow down—then you could still have a deflationary situation. So, given all of that that we talked about, and actually, I want to make another point. In the early 70s, everyone always talks about the oil shock, right? In 1973, you had the Yom Kippur War; we resupplied Israel, and then you had all the OPEC countries that essentially stopped selling oil to the U.S. and a lot of other Western nations. People say, you know, oil prices shot through the roof, and that's what drove inflation. That supply shock probably contributed to it, but 1973 is right around there. So if you actually look at this chart, we were already kind of on an inflationary spectrum; generalized prices were already increasing, and capacity utilization had really preceded that. That probably just added fuel to the flame. With that said, everyone, you know, the question that everyone's wondering about is: what's going to happen now? So before the current financial crisis, let me just say we had a certain amount of capacity. Let's say this is everything; this is the U.S. output. U.S. output, and in a normal environment, let's say this is U.S. GDP, right? Output—GDP is just output. So in a normal developed environment, if you go back into the 60s, we consumed about 60% of our GDP on consumption. Consumption isn't always a bad thing. It's actually what we use to have a good standard of living. You know, if I have a nice sofa and a TV set and I go on vacations, that's consumption, but it improves our standard of living. The goal of all countries is really to improve that average standard of living. But the remainder is savings. In a traditionally responsible developed nation, you save 30% to 40%, depending on whether you're Japan or whether you're Western Europe. What savings turns into is essentially new investment to raise your output. So this savings is what allows you to increase your output in the next year. If you don't save even a little bit, your output will actually decrease because no one will invest in factories, and the factories will get old, and the roads will stop being usable. Whenever someone's investing, that's someone else's savings, and it's very important to realize that investment and savings are really two sides of the same coin. If no one's saving, then there's no money for investment. But just going back to this example, when people are saving, that's what not only maintains output but actually increases total output. So this would be, you know, the next year or the next decade. When we consume 60% of this, we're consuming 60% of a large number, and our standard of living will go up. This is a very sustainable and good situation. What happened, unfortunately, over the really since the early 80s is that we had a constant expansion of credit, and we started lending more and more money to everyone. Other countries started lending more and more money to us, and most of that got expressed in more and more consumption. So if you look at U.S. output—if you go to 2007, the average American consumed more than we produced; we had negative savings. If I were to draw that, it looks like this: in 2007, consumption was larger than our total output. So the question is, how did this happen? Well, essentially, if you, you know, let's put all—everyone talks about money in currencies. Essentially, we borrowed output from other people. When we borrow money from the Chinese, which we use to buy their goods, we're essentially just borrowing their output, right? We're borrowing their goods. When we give them a dollar bill, that's a promise that in the future they could use that dollar bill to come back and use some of our output. But over the course of the last several decades, we were just borrowing other people's output, and we became net debtors. So when your consumption is actually larger than your output, you immediately start to realize that this isn't a sustainable situation for too long. Maybe we borrowed a little bit more money, and it actually did turn out that way—that we borrowed some people's output even more to fuel some of our investment as well. It's not like no investment was going on for the last 20 or 30 years; we had a lot of investment, but it was essentially being financed by other people's output. Of course, when you have consumption kind of touching up against, you know, your fully utilized, that makes even more incentive to invest. So all of these people were willing to invest in the U.S. What happened now is you realize that a lot of this—the financing or a lot of the debt that was being taken on was, you know, it was being facilitated by people's homes and home equity loans, but people really aren't good for it. Now, all of a sudden, the banks have dried up; liquidity is gone, people can't borrow money, and you have a demand shock. So what you have is a situation where a considerable amount of this consumption—and actually a good considerable amount of that investment that was being fueled by financing—disappears. Now that we're in a global world, we really should think about global output, but it doesn't matter; we could talk about just U.S. output. Now that this demand has disappeared, if this is U.S. output, and let's say this is output that, you know, we were taking from China or Japan or wherever else, and our consumption has now fallen down here, it's not because all of a sudden people became prudent; it's because people aren't willing to lend them to go to Williams Sonoma and buy a $50 spatula or whatever else. They just can't get another credit card loan or a home equity loan. So you have the situation now where you have low utilization. This comes back to what we talked about in the last video: when you have low utilization, it's everyone's incentive to lower prices. When you have a bunch of vacant houses, people lower rents. When the car factories are empty, people lower the price of car factories. When people are underutilized, wages go down. You see this shock more recently right here, as we expressed. We said in the last video, the orange line is U.S. capacity utilization, and it dropped from, let's see, that was about the 80% range. If it had gone up here, I would have started getting worried about hyperinflation. But you see, right around summer of 2007, it dropped off a cliff, and it's down here someplace. As you see a little bit later, inflation dropped. So that dynamic that we've been talking about—capacity utilization falling off because we essentially had a demand shock—and then that's led to a decrease in prices. So the question is: everything that the Treasury is doing and the Fed is printing money, and Obama spending a trillion dollars in stimulus, is that going to lead to inflation? My answer is just watch the capacity utilization numbers. Just so you know, the stimulus plan—the whole idea about it—is they didn't want us—the government doesn't want us to enter into a deflationary spiral. Because if consumption drops like this, we have all of this capacity, and prices go down. If prices go down a little bit, it doesn't affect people's behavior in aggregate. But if people start having an expectation that wages will go down, that prices will go down, then they all go into panic mode and they stop spending. Then utilization, you know, let's say they stop spending, stops spending, then utilization goes down even more, then unemployment goes up even more. This also makes fear go up even more. Unemployment going up and fear going up makes people stop spending even more, and this is that deflationary cycle that all the economists and all of the government officials are afraid of. You saw that during the Great Depression. Right here, let me draw a zero point to show you where. So if this is zero, that is zero. Let me draw it further. That's the dividing line between inflation and deflation. You see we've had a couple bouts of deflation, and they normally aren't good times in the world. This is the Great Depression right here. This is post-World War I, and the Great Depression actually lasted all the way until, see, we entered the war in the late 30s. So it's right about here to here. We had a little bit of inflation; you had the first wave of the New Deal stimulating some spending, but it really never got us to any significant level of inflation. Just so you have a sense, I would consider anything above 5% inflation is kind of really, really bad. Let me draw a line there, so that's kind of the 5% inflation mark. You see we really didn't get above 5% inflation until you end up with World War I, and then you have the post-war period under Bretton Woods. Then in the 70s, we had the—as I talked about before—you know, you had the oil shock and all the rest, and, you know, the rest is history. But as you see, the deflationary periods were just things that government officials want to avoid altogether. The idea of the stimulus is for the government to borrow money because no one else can, and they can essentially fill up the gap where the consumer left off. Now the question is: are they going to fill up enough of a gap? And actually, I realize that I'm running out of time again. I don't like to make these videos too long, so I'll talk about that in the next video.

Залогинтесь, что бы оставить свой комментарий