|  |  | |||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|  |  | |||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

Техническая поддержка

ONLINE

|  |  | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

Inflation and deflation 3: Obama stimulus plan | Finance & Capital Markets | Khan Academy

ruticker 08.03.2025 21:05:03 Recognized text from YouScriptor channel Khan Academy

Recognized from a YouTube video by YouScriptor.com, For more details, follow the link Inflation and deflation 3: Obama stimulus plan | Finance & Capital Markets | Khan Academy

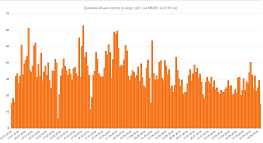

I finished the last video touching on the stimulus plan and whether it's going to be big enough and what its intent was. But I was a little hand-wavy about things like savings and GDP, and I thought it would actually be good to get a little bit more particular just so you know that this isn't just me making up things. A good place to start is just to think about **disposable income**. People talk about it without ever giving you a good definition. It's important to understand what disposable income is. So, this box right here is GDP. It's all the goods and services—essentially, all of the income that we produce. The disposable income is essentially the amount that ends up in the hands of people. The U.S. GDP, I don't know what the exact number is; it's on the order of, I think it's like **$15 trillion**. Whoops! It's on the order of **$15 trillion**. Some of that money goes to taxes. I don't know, maybe **30%**—let's just say **$4 trillion** of it. Let's say **$3 trillion** ends up in taxes. These are round numbers, but it gives you a sense of the makeup. Then maybe about another **$1 trillion** is saved by businesses. So, let's say that I'm Microsoft and I make a billion dollars this year. Microsoft makes a lot more than that, but I make a billion dollars and I just keep it in a bank account owned by Microsoft. I don't give it to my employees; I don't dividend it out to the shareholders; I just keep that. So, corporate savings—let's say it's another trillion dollars. These are roundabout numbers, and then everything left over is essentially disposable income. I'm making some simplifications there, but everything left over is disposable income. The idea is, what is in the hands of households after paying their taxes? Disposable income—that check that you get after your taxes and everything else is taken out of your paycheck—that money is disposable income to you. So, the interesting thing is where this disposable income has been going over the last many years. This chart right here—actually, let me go down a little bit—this right here, this chart is a plot of the percentage of disposable income saved since **1960**. I got this off the Bloomberg terminal. Again, just so you get a good reference point, let me draw the line for **10%** because I kind of view that as a reference point. That's **10%** personal savings. Actually, you could go back even further than this, and you could see from the **1960s** all the way until the early **80s**—the go-go **80s**—people were saving about **10%** of their disposable income, of what they got on that paycheck after paying taxes. They were keeping about **10%** of it, putting it in the bank, and of course, that would then later be used for investment and things like that. But then, starting in the early **80s**, right around, let's see, it's about **1984**, people started saving less and less money, all the way to the extreme circumstance of **2007**, where on average, people didn't save money. Where, you know, maybe I saved five dollars, but someone else borrowed five dollars. So, on average, we didn't save money; actually, we went slightly negative. And all of this—and this is kind of my claim, and it can be borne out if you look at other charts in terms of the amount of credit we took on—is because we took on credit. I guess there are two things you could talk about: we took on credit, and we started having what I call **perceived savings**. If I buy a share of IBM, a lot of people say, "Oh, I saved! I saved my money; I bought, you know, I'm invested in the stock market." But when I bought a share of IBM, unless that dollar I paid for the share goes to IBM to build new factories—if it—and that's very seldom the case. Most of the time, that dollar I gave to buy that IBM share just goes to a guy who sold an IBM share. So, there's no net investment. It's only savings when that dollar actually goes to invest in some way—build a new factory or build a new product or something. So, I think you had more and more people thinking that they were saving when they weren't—maybe thinking that they were saving as their home equity and their house grew or as their stock market portfolio went up. But there wasn't actual aggregate savings going on. In fact, if anything, they were borrowing against those things, especially home equity, and the average saving rate went down and down and down. So now we're here in **2007**, and maybe you could say, you know, **2008**, where let's say that this is the capacity. We should probably talk about world capacity because so much of what we consume really does come from overseas. But this is kind of the capacity serving the U.S. and let's say going into **2007**, this was demand. Supply and demand was, let's say, pretty evenly matched, right? And if we go to that top up here, you see that we weren't at like kind of a—you know, we were at like **80%** utilization, which isn't crazy. So, if anything, you could say that we had, you know, demand was maybe right around here, but that's a good level. You want to be at around **80%** utilization; that's the rate at which you don't have hyperinflation, but you're utilizing things quite well. Now, all of a sudden, the credit crisis hits, and all of this credit disappears. I'd make the argument that the only thing that enabled us to not save this money is more and more access to cheap credit. Every time we went through a recession from the mid-**80s** onwards, the government solution was to make financing easier. The Fed would lower interest rates; we would pump more and more money into Fannie and Freddie Mac; we would lower standards on what it took to get a mortgage; we would create incentives for securitization; we would look the other way when Bear Stearns was creating collateralized debt obligations or AIG was writing credit default swaps. All of that enabled financing, right? Until we get to this point right here where everything, everything, everything starts blowing up. So, you essentially have forced savings when people can't borrow anymore. The savings rate is going to have to go to **10%** because most of this is just from people taking on more credit. There was a group of people who were probably always saving at **10%** of their disposable income, but they had another group of people who were more than offsetting that by taking credit. Now that the credit crisis hits, you're going to see the savings rate—and you already see it here with this blip right there—the savings rate is going to go back up to **10%** of disposable income. Now, if the savings rate goes back to **10%** of disposable income, that amount of money—that **10%** of disposable income—this gap is **10%** of disposable income that cannot be used for consumption. Right? And let's think about how large of an amount that is. Right now, U.S. disposable income, if I were to draw disposable income, this number right here—I just looked it up—it's around **$10.7 trillion**. Let's just say **$11 trillion** for roundabout. So, this **10%** of disposable income that we're talking about—this gap between kind of the normal environment and what people—the environment that was enabled from super easy credit—that's **10%** of disposable income. **10%** of **$11 trillion** is **$1.1 trillion** per year of demand that will go away. That's per year! So, all of a sudden, you're going to have a gap where this was the demand before, and now the demand is going to drop to here. And all of this **$1.1 trillion** of demand is going to disappear because credit is now not available. And then you do get a situation where you might hit a low capacity utilization. Unfortunately, the capacity utilization numbers don't go back to the Great Depression, and we could probably get a sense of at what point does a deflationary spiral really get triggered. But because at one point **$1 trillion** in demand disappears, you're going to see this orange line just drop lower and lower in terms of capacity utilization, and that's going to drive prices down. What Obama and the Fed and everyone else is trying to do is to try to make up this gap. Now, everyone else can't borrow money; companies can't borrow money; homeowners can't borrow money. But the government can borrow money because people are willing to finance it, or at the bare minimum, the Fed's willing to finance the government. So, the government wants to come in and take up the slack with this demand and spend the money themselves with the stimulus. Now, we just talked about what's the magnitude of this demand shock—it's **$1.1 trillion** per year, right? **$1.1 trillion**. While the stimulus plan is, you know, on the order of **$1 trillion**, and that **$1 trillion** isn't per year, although I have a vague feeling that we will see more of them coming down the pipeline. This **$1 trillion** stimulus plan that just passed is expected to be spent over the next few years. So, in terms of demand created over the next few years, it's going to be, I don't know, several hundred billion per year. So, it's going to be nowhere near large enough to make up for this demand shock—to make up for that demand shock. So, we're still going to have low capacity utilization. So, the people who argue that, you know, these stimulus plans are going to create hyperinflation—I disagree with that, at least in the near term. Because in the near term, it's nowhere near large enough to really soak up all of the extra capacity we have in the system. And if anything, it's going to soak up different capacity. So, the stimulus plan might create inflationary light conditions in certain markets where the stimulus plan is really focused. But other areas where you used to have demand, but the stimulus plan doesn't touch—like **$50 spatulas** from Williams Sonoma or granite countertops—that area is going to continue to see deflation. And I would say, net-net, since the stimulus is actually so small, even though we're talking about **$1 trillion** relative to the amount of demand destruction per year, we'll probably still have deflation. And for anyone who's paying close attention to it—and I am because I care about these things—the best thing to keep a lookout for to know when to kind of start running to gold, maybe, or being super worried about inflation is if you see this utilization number creep back up into the **80%** range. And you know, at least over the last **40 years**, that's been the best leading indicator to say, "When are we going to have inflation?" And for all those gold bugs out there who insist that all of the hyperinflation or the potential hyperinflation is caused by our not being on the gold standard, I just want to point out that you can very easily have—you know, we went off of Bretton Woods and completely went to a fiat currency in **'73**. That's right around, let's see, **'69**—that's right around here. But our worst inflation bouts were actually while we were on the gold standard, and that's because we had very high capacity utilization. This is the war beard. What happens during a war? You run your factories all out; you run your farms all out to feed the troops. The factories, instead of building cars, build planes, and everyone is working. Wages go up; everything goes up, and you have inflation. Right? And a lot of people say that, "Oh, you know, the war was the solution to the Great Depression." And it is true in that it got us out of that deflationary spiral that I talked about in that last video, and it did it by creating an unbelievable amount of inflation. And then after the war, you could argue—you know, I don't have GDP here, but the U.S. GDP really did do well in the post-war period. And it wasn't the war per se, although the war kind of did take us out of the deflationary spiral. It was, you know, after the war, you had all of this capacity. After World War II, see all this capacity that was being used up by the war? Then all of a sudden, the war ends, and you're like, "Well, we don't have to build planes anymore; we don't have to feed the troops anymore." And now we have all these unemployed troops who come back home. What are we going to do with them? Right? You would say maybe capacity utilization would come back down there. But what a lot of people don't talk about is the rest of the industrial world's capacity was blown to smithereens at that point in time. The U.S. was a smaller part of GDP, and the other major players were Germany, Western Europe, and Japan. All of these guys—in the U.S., we didn't have any factories bombed. All of the entire war took place in these areas. And whenever people go on bombing raids, the ideal thing that they want to bomb is factories. So, what you had in the post-war period is you had all of these countries had their capacity blown to smithereens. The U.S. was essentially the only person left with any capacity. And so all the demand from the rest of the world picked up the slack in the U.S. capacity. And that's why, even though there was a demand shock in the U.S. after that, you had demand from—you also had a supply shock from the war, where you had all of this capacity that was blown to smithereens. In this situation that we are now, we have a major demand shock, right? Financing just disappears, and the savings rate is going to skyrocket because people can't borrow anymore. But there's no counteracting supply shock, right? The supply of really, you know, factories making widgets and all the rest is staying the same. So, the Obama administration, they're trying to create a stimulus to stop some of this up, but it's not going to be enough. And my only fear is with all of the printing money and all that goes—is once we go to a situation, once we do get back to the **80%** capacity utilization, once we do go back here, how quickly they can unwind all of this printing press money and all of the stimulus plan. Because that's going to be the key. Because if we do get to **80%** capacity utilization or we start pushing up there and we continue to run the printing press—because that's what essentially the government's incentive is to do, because they always feel better when we're flush with money—then, and only then, you might see a hyperinflation scenario. But I don't see that, at least for the next few years.

Залогинтесь, что бы оставить свой комментарий